The Cassin Collection at Auction (III) Jack Runs the Voodoo Down

The third part of the series on the occasion of the upcoming sale of Jack Cassin's collection is about Anatolian kilims. Jack had been lucky enough to find his masterpieces already in the late 1970s, before a British archaeologist, James Mellaart, became involved and Anatolian kilims became so popular.

It was in fact Cassin, the spin doctor, who had contacted Mellaart in the early 1980s, and both developed the idea that Anatolian kilims might echo cults in neolithic societies of that region, an absurd and ludicrous hypothesis to the extreme. Textile and weaving expert Marla Mallett had long debunked the major claims in Mellaart, Hirsch and Balpinar's Goddess of Anatolia (1989) as utter nonsense.

Cassin, who had initiated the project, later withdrew his collaboration when he noticed, already in the 1980s, that Mellaart was a fraud who had invented findings at the Çatal Hüyük excavation site in Anatolia. Cassin wrote about that in some detail in what he called his Anatolian kelim opus.

That Mellaart was a fraud was confirmed long after this in 2012 by German archaeologist Eberhard Zangger. Zangger had even visited Cassin in New York and got first-hand information about Mellaart's scientific fraud. In 2015, I had informed Cassin about a new website by Zangger, Luwian Studies, where he listed among pioneers of Anatolian archaeology James Mellaart. So, it was actually me who draw his attention to Zangger whom he then met in New York.

In 2018, Zangger wrote an article about Mellaart's fantasies (Talanta L 2018, 125-182) where he writes, on p. 140,

“In December 2017, I was able to speak to Jack Cassin, an Anatolian carpet and kilim researcher, collector and expert, who had conceived the original concept for The Goddess from Anatolia. Mr Cassin spoke at length with me and kindly provided an insider’s perspective on what had happened at the time. While looking for the iconographic roots of the designs on the earliest Anatolian kilims, his research led him to James Mellaart’s discoveries of Çatalhöyük and Hacılar. After tracking Mellaart down to his office at the London School of Archaeology in Gordon Square, Cassin proposed that he and Mellaart work on a book together. This was in late 1980, and over the course of the next two years, Cassin spent many hours and days with Mellaart. Eventually, in 1983, Mellaart agreed to co-author a book with Cassin, who also enlisted Belkıs Balpınar and Udo Hirsch. That book was provisionally titled 9,000 Years of Anatolian Kilim.Over the ensuing four-year period, Cassin and his co-authors were working on their contributions when Mellaart began to show Cassin newly reconstructed drawings of Çatalhöyük wall paintings (e.g. Fig. 2). Seeing these, and noticing the blatant differences between them and the others already published in Mellaart’s excavation reports of each season’s digs, Cassin became suspicious. When Mellaart presented reconstructions of an erupting volcano and men and women making love, Cassin knew he had to either confront Mellaart, and possibly destroy their friendship, or withdraw from the project and publish his own book. He chose the latter approach and sold the 9,000 Years of Anatolian Kilim book project to the Milan rug dealer John Eskenazi, who then published the book under the new title The Goddess from Anatolia. Cassin himself produced his limited-edition publication entitled Image Idol Symbol: Ancient Anatolian Kilims (Cassin 1989) which appeared shortly before The Goddess from Anatolia, and included genuine verified archaeological materials, particularly Palaeolithic and Neolithic female effigy figures and wall paintings.”

Well, fantasies is what makes an archaeologist. Zangger, who once fantasized about Atlantis, which he located in Troy, knows too well. His late nemesis, Manfred Korfmann, fantasized, in 1994, about a vast suburb outside the walls of Troy’s acropolis (the year before, he had called Troy a pirates’ nest), was called “Däniken of archeology” by his adversary, Dr. Frank Kolb. They all “reconstruct” history. And (intentional or unintentional) forgeries are part and parcel. Remember Sir Arthur Evans, who “reconstructed” murals in Knossos?

The mere claim that iconic elements in contemporary weavings may have their origin in Neolithic iconography (as is suggested in the defunct title of the book by Mellaart, Balpinar and Hirsch, 9000 Years of Anatolian Kilim) is and always has been laughable. That meanwhile disgraced individuals in the antique carpet business used Mellaart for their own agenda is another thing.

It’s important to keep in mind Mellaart’s forgeries. They are (p. 54 of Zangger’s article):

1. The Dorak treasure

2. The “sketch reconstructed” wall paintings from Çatalhöyük which he presented more than twenty years after his excavations

3. The translation of alleged bronze tablets said to have been found at Beyköy, the so-called Beyköy Text.

But I distract.

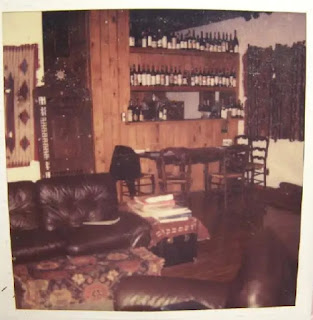

The photo, published in his Anatolian kilim opus (p. 52), shows Cassin's living room in Greenwich Village in ca. 1982. It proves that Jack owned then at least two of his now world-famous archetype and classic (according to his definitions) kilims which can be seen hanging on the wall. Both are prominent featured in the upcoming sale. It also proves that Jack had another passion as he was also a wine connoisseur. And loved to surround himself with his antique finds which he did not put on the floor but on tables.

The overall furnishing is middle-class, rather petty bourgeois. How different is the living room of his arch enemy, Dennis Dodds, who boasts his taste and abundance, including the infamous Bellini carpet on one wall, in several pictures on his website, maqam-rugs.com.

According to his Anatolian kilim opus, Jack had not been interested in collecting kilims before 1979. He is convinced that one cannot possibly hope to find or purchase great archetype Anatolian kilim today anymore. He got his collection of respective pieces, just nine or ten, during a very short period of time when a very small number of extant archetype kilim came out and onto the market.

For that reason, the upcoming sale at auction may be such a great opportunity for, well, the super-rich.

Let us start with the two kilims hanging in Cassin's living room on the wall in 1982.

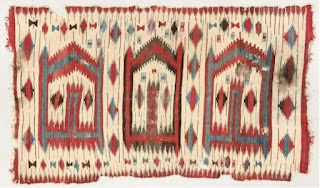

The upper one is a most beautiful saf kilim (assigned to Karapinar by the auction house, 18th century; lot 25) with three niches. Obviously a masterpiece, according to Cassin from the early classic period. In general, it is Islamic art. I have long been dismayed when many dealers and collectors of Anatolian kilims have denied the strong Islamic influence. One has to realize that the members of these tribes are devout Muslims, connected to the local mosques. They are not descendants from neolithic societies practicing shamanism. Or Zoroastrians placing their deceased on so-called towers of silence for being devoured by vultures.

Cassin's saf kilim has three prayer niches and should be directed towards Mecca. As it is two meters wide, one can in fact imagine that three members of a family would pray on the kilim in the Mecca direction. The so-called (by Cassin) archetype is in Berlin's Museum of Islamic Art and that kilim features lamps in each of the niches. That refers to the mystical Light Verse in the Qur'an (Q24:35):

</“God is the Light of the heavens and the earth.The parable of His light is, as it were, that of a niche containing a lamp;the lamp is [enclosed] in glass,the glass [shining] like a radiant star:[a lamp] lit from a blessed tree –an olive-tree that is neither of the east nor of the westthe oil whereof [is so bright that it] would give light [of itself] even though fire had not touched it:Light upon Light!God guides unto His light him that wills [to be guided];and [to this end] God propounds parables unto men,since God [alone] has full knowledge of all things.”

That Cassin's kilim doesn't display lamps in the three niches doesn't mean that this is not sacral object meant for praying. The direction is there, three devout Muslims can pray there together, maybe on Friday prayers. It is certainly the best of the group.

The kilim does contain numerous artistically elaborated devices other than lamps. Cassin argues that this might have been proscribed in older safs. Maybe because Islam proscibes floral depictions? I don't know whether that criterion suffices to put the textile in its continuum later than Cassin's archetype in Berlin. As compared to comparable saf kilims in the former Poppmeier and Vok collections, Cassin's (who compares his with even more examples, see p. 58, 59) clearly stands out. The weaver's beautiful execution of the design with numerous small motifs is crucial. The Poppmeier (top) and Vok (bottom) examples are utterly stiff in comparison, boring; although both contain lamps in the niches. They may represent the Islamic proscription of not distracting the devout prayer. Cassin's, in comparison, represents the weaver's artistic great talents. Judge for yourself, which one would you prefer? Maybe the later example (Cassin's?) was the far better?

Let's now turn to the second kilim in Cassin's living room in 1982, the gorgeous Balikesir. Cassin never used this assignment for his find from the late 1970s, early 1980s. But Cassin found and purchased it in the US. Nobody knew anything about that kilim then. And Cassin was never interested in ethnological research.

In 1986 (Seltene Orienttepiche 8, plate 15), Eberhard Herrmann had assigned this group of kilims to the Balikesir province in the Marmara region of modern day Turkey. It is possible that it was woven by Yüncü nomads living there. As very few original examples of this group had emerged over the years, this must be considered pure specuation. Yanni Petsopoulos has a similar piece in his book, 100 Kilims, of 1991 (plate 15; see it copied in the Anatolian kilim opus, p. 111 and p. 136).

Herrmann's kilim had been purchased by Ignazio Vok (below, left), and a comparison makes clear that Cassin's is the far better, and older; actually, again the best of this small group.

The next kilim in the upcoming auction I want to address (lot 26) is one of a pair which Cassin had bought already in 1979 in New York from a foreign dealer who he knew that he traveled to Istanbul frequently.

Jack had shown him pictures of what he would like to buy. The story of the purchase, to be read in his Anatolian kelim opus, (p. 12, 13) is quite amazing. It suggests an almost erotic encounter with Jack seducing a mildly intoxicated (with a bottle of 1959 Lafite Bordeaux) dealer in his own apartment to sell him the two pieces which had actually not been for sale.

As can be seen, the two kilims are similar, though maybe not woven by the same weaver. They clearly belong to the same group. But the one not at auction (bottom) is far more interesting with its dramatic and vibrant drawing and varying smaller motifs. As I have outlined in the beginning of this post what one has to think about Neolithic artifacts and absurd associations when looking at the main design elements of these two kelims, I do not want to repeat myself. That should be discussions of the 1980s and science has moved on since then.

The auction house estimates that the Hotamis kilim (above, top) was done in the 17th or 18th century. Its companion (at the bottom of the above picture) is not at auction, as is not another of Cassin's stellar kilims (see below). I am afraid, Cassin had to sell them (and even more, see below) for paying hospital expenses before he died.

That these kilims are so very special may not be recognized by many pundits who have not seen them "in the flesh". When Jack decided to discuss his collection on Facebook in 2017 (see my previous blog post), there had been a fierce discussion about archetypes, icons and provenance etc. The above kilim was easily assigned to Aydin in Western Turkey by the FB group administrator, based on similar kilims from that area. That may well be. Cassin himself offers another location as he had found a very similar kilim, on his road trip to East Anatolia in 1981, in the Esrefoglu mosque in Beysehir. Of course, it may have been dropped there by tribesmen from Aydin in fact hundreds of years ago.

The above picture is a polaroid which Jack took in 1981 in Beysehir's mosque, showing that very similar kilim in situ (p. 114). These white-ground kilims may have been used in funerals as Cassin mentions. So, the natural place for storage of these beautiful weavings was probably a mosque.

It is hoped that these two absolutely outstanding kilims (the latter and the companion of that presently at auction) will surface one day.

Of Cassin's gorgeous collection of ten archaic or classical kilims (see above), seven are for sale at the auction.

Comments