Bazm Wa Razm

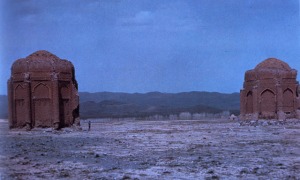

I have written about the two Kharraqan towers before, see here. Both had been heavily damaged in a 2002 earthquake. They are located about one km west to the village of Hisar-i Valiasr and 33 km west to Ab-i Germ on the Qazvin-Hamadan road in the Qazvin province.

The towers are basically octagonal with a height of about 15 meters and a width of 4 meters. They are considered the earliest examples of double-domed buildings in Iran.

Due to their extraordinary ornamental brickwork the Kharraqan towers belong to the finest Seljuq monuments found in Iran. Execution of artistic ambition directly relates to that of the Maraghah towers, see here. They were built by Muhammad b. Makki al-Zanjani in 1068 and 1093 CE. It is amazing that they had been discovered in the west not before 1963 by William Miller and described shortly afterwards by archeologists David Stronach and T. Cuyler Young Jr.

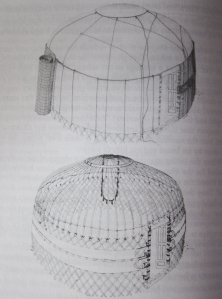

The Kharraqan towers are tombs, and the occupants are most likely unknown Seljuq chieftains. The towers resemble in fact typical trellis tents, then so-called khargahs, which are still in use by Turkmen tribes.

Nomad Rulers and Cities in Iran

After a successful siege of Isfahan in 1050/51 by Toghril Beg it is usually held that the city had been made a capital of the Seljuq empire under one of his successors, Malikshah I. One might wonder, though, what "a capital city" actually means for nomads such as the Seljuqs. It is amazing to read that this question has largely been ignored until very recently.

Isfahan is still home of most impressive Seljuq monuments. I have written about the stunning Friday mosque many times on this blog, see, for instance, here and here. While construction of the larger south dome had been commissioned by Malikshah in 1087, the awesome and almost perfect north dome was built on request of Taj al-Mulk, arch enemy of vizir Nizam al-Mulk, just one year later.

In addition to the Friday mosque, which displays an amazing plurality of Seljuq, Il-Khanid, Timurid and Safavid architecture, Isfahan's old city is home of a couple of surviving Seljuq minarets, for instance the minaret of the Ali mosque (ca. 1200), the Sareban minaret (both 50 meters tall) and the 29 meters tall Chehel Dokhtaran minaret (1107/08). Far more of such buildings can be found in the countryside.

But where has the palace of the sultan been? A recent study considerably substantiated the hypothesis that Seljuq chieftains did not live in cities at all [2]. They lived in luxurious tents pitched in vast camps outside the city walls.

In the first half of the 11th century, Isfahan had been ruled by local Kayukid emirs, in particular Ala al-Dawla Muhammad (d. 1041) who had invited Ibn Sina (Avicenna, d. 1037) to his court. Since 1029, the city had been under attack several times by Turkish military powers, first the Ghaznavids, then the Seljuqs.

When the Isfahanian citizens finally opened the gates in 1051, Toghril had decided to spare the city. One of the main reasons was that he strove for the title of sultan conferred to him by the Abbasid caliph al-Qa'im in Baghdad. The conquest put an end to twenty years of war.

Court and Cosmos

When hordes of Seljuq Turkmen invaded the high plateau in the early decades of the 11th century Iran experienced an unexpected blossoming of art and science. An exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with just 250 objects (for instance gold and silver-inlaid brass ewers, basins or candle stands, glazed fritware, gold coins and jewellery, illuminated Qur'ans) on display until 24 July paints a picture of the rather pleasant and luxurious life of noblemen and members of the middle class alike who engaged in hunting, fighting and feasting (bazm wa razm).

One may in fact ask (as the New York Times does), What is actually genuinely nomad Seljuqian?

"While all of this testifies to an aesthetically and technologically sophisticated culture, a nonspecialist might wonder what is distinctively Seljuqian about it — what distinguishes it from, say, medieval Islamic arts and crafts in general. Nomadic invaders from Central Asia, the Seljuqs did not impose on their subjects a traditional aesthetic or religion of their own. Rather, they commissioned artistic and decorative works from artisans of various subject peoples. They built palaces, mosques, madrasas and hospitals in Islamic architectural styles. But what the Seljuqs created most consequentially was a relatively peaceful, prosperous and unified world wherein indigenous literature, arts and sciences were able to flourish in urban centers throughout the region."The beautifully written and carefully edited catalog of the exhibition [3] provides invaluable further information about this rather short-lived dynasty of sultans who had conquered much of the then known world.

Notes

[1] Durand-Guedy D. Tents of the Saljuqs. In: Durand-Guedy D (ed.) Turko-Mongol Rulers, Cities and City Life. Brill: Leiden, Boston 2013, pp. 149-190.

[2] Durand-Guedy D. Iranian Elites and Turkish Rulers: A History of Isfahan in the Saljuq Period. Routledge Studies in the History of Iran and Turkey. Routledge: London, New York 2010.

[3] Canby S, Beyazit D, Rugiadi M, Peacock ACS et al. Court and Cosmos. The Great Age of the Seljuqs. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2016.

First published at Freelance.

Comments