"Why Michael Franses?

Well, I suppose because he represents one large tail of the rug dealers’, highly skewed-to-the-right, distribution. Having tried for decades to paint himself an expert and collector of high-end oriental rugs and honorable dealer, the façade has apparently crumbled. That the Bellini carpet (the object of probably the most egregious fraud of the past 20 years or so in the world of antique rugs) was in his possession before he sold it to Dennis Dodds, I had also noted some time ago when browsing the internet. I did not pay too much attention then since I liked the decoration of Dodd’s home with certainly highly valuable pieces anyway, most probably the only honest reason why rich individuals should collect antique rugs: to display them at home not store them in an inventory.

It’s interesting that a simple sting operation exposed Mr. Franses true colors to the interested public. Franses enjoys now, as an employee of the Qatar Museums Authority, life in one of the hottest and unfortunately most humid environments in the world where slave labor is most common while freedom of press and opinion are severely restricted. He seems to spend his off time, when not musing about “fast boat services” on Qatar’s most beautiful Corniche (http://www.gulf-times.com/opinion/189/details/340415/letters-to-the-editor) or “light pollution” and the stars over Doha (http://www.gulf-times.com/opinion/189/details/345448/letters-to-the-editor), which he actually doesn’t know (at least not to that extent of Kirchheim’s Orient Stars), with hooking certain super-rich fellows to unlawfully buy items from his inventory under most conspiratorial circumstances. It is revealing that Mr. Franses appears not to be too much afraid of being fired by his Qatari superiors for severe conflict of interest, but that exposure of the email exchange with Jack would tremendously affect the prices of his rugs he might have achieved when dealing with an apparently unknown, so naïve, would-be collector from Germany. All of this is most appalling.

One further remark. Jack’s most educational description of the pieces and comparisons with the real stuff is highly appreciated as it may be regarded not at least a strong warning not to listen to the baseless blabber of rug mongers, be it those who deal with high-end-nearly-museum pieces, or dwarfs who use to cheat twice (or actually three times), first the deliveryman in Istanbul, then the would-be “collector” and finally tax authorities in, say, Germany."

In 2014, Jack Cassin started a sting operation to expose one of his main adversary's, Michael Franses', shady business practices. While Franses was employed by Qatar's Museum Authority and therefore prohibited from continuing selling as a carpet dealer, Cassin contacted him via email and pretended to be a super-rich, albeit "naive", German collector in search of antique pieces. The full story was published, in several installments, on

RugKazbah, a website which is now defunct. The above commentary, which I posted in response to one installment about Franses' attempt to do business with a German super-rich customer may in fact illustrate the problem with naive novices when contacting supposed or self-proclaimed experts who just turn out to be greedy predators.

Regardless of the simple fact that Cassin always considered his pieces way superior than comparable ones in other collections or on the market, the only way how to educate the novice is to painstakingly analyze and show the differences. And that is what he did in his installments on Franses and otherwise.

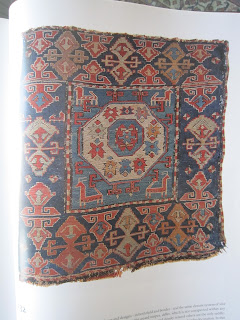

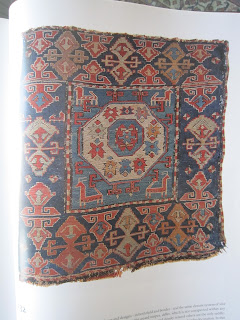

The above bag face, or khorjin, has nothing to do with Cassin's sting operation of 2014. Nor is this particular half-khorjin offered for sale at the upcoming auction. It seems that Cassin had owned both parts of the double bag. The above had been published by

John Wertime in 1998 (plate 132) and probably sold by Cassin afterwards. It is the other bag face that is now

for sale at the auction (lot 6).

Although on first sight not spectacular, not even outstanding, the above khorjin is in a way most interesting. There seem to be three published variants of it, and experts do not agree on provenance. Cassin, when I had asked him, was hesitant to assign any of his (or other's) khorjins to any particular tribal group. Wertime assigns this particular bag face to the Khazaks. He compares it with an, in my opinion, much younger one (plate 131).

Wertime argues,

"A large ivory-ground octagon with hooks in the centre of the field is a motif that occurs in rugs of the Kazakh type from Karachop village in the Borchalu district of southern Georgia.196 It is also found in sumak bags apparently made in the same area or in the adjacent Kazakh district, judging from a bag in Salahli (a town situated near the Kor river north of Kazakh town), during an expedition in 1928 sponsored by the Azerbaijan State Museum (fig. 31, p. 205).In addition to a sigificant design similarity, these pile rugs and sumak bags share a similar palette. Were they made by the same or related people? I know of no bags with this distinctive motif from elsewhere in northwest Persia or Transcaucasia."

Wertime estimates that both bag faces were made in the last quarter of the 19th century, but Cassin's seems to be much older. The corresponding khorjin face (which is for sale at the auction) is described early/mid 19th century. But here it is assigned to the Shahsevan. Eminent Iranian scholar, expert of tribal weavings and sculptor, Parviz Tanavoli, describes, in his book Shahsevan of 1984, a third comparable bag face. He assumes that it had been made in the early 19th century.

When these khorjins are compared, it should be clear that Cassin's stands out. The design is more primitive, but certainly more spacious. The weaving appears not very elaborated. There is much more overall patina, while the ivory ground of the octagon is rather dull.

It is not far-fetched to assume that Tanavoli's is a later imitation, by the Shahsevan of the Moghan plane (as suggested; i.e., several hundred kilometers southeast to Khazak), of Wertime's plate 132 (Cassin's), which is the much earlier khorjin, meaning the original, and which actually is Kazakh/Karachop. As the overall appearance and carefully elaborated sumakh of Wertime's plate 131 khorjin is actually a Shahsevan imitation or originates also from the Kazakh may be debated.

Neither spectacular, nor outstanding is also the above khorjin face which is assigned, by the auction company, lot 20, to the "Shahsevan, Transcaucasus, mid 19th century". Again, I doubt whether Cassin himself would have agreed. (I assume, this and lot 16 were pieces he just bought for quickly selling them afterwards and making some profit.) The grid of hexagons with a cruciform motif is often found in textile designs by weavers from the Bakhtiyari/Luri tribes. Complete bags have usually a pile bottom. The color palette differs. Wertime's (1998) plate 136 displays a typical example. Wertime cautions his readers, though, that the design (cruciform motif in a grid of hexagons) may also be used by the Shahsevan, see plate 23. However, the palette and border designs differ largely. Cassin's may in fact be Bakhtiyari/Luri rather than Shahsevan. The same may apply to lot 16.

The confusion about this essentially Bakhtiyari/Luri design is widespread. I had bought a quite charming bag face of obviously some age from a German dealer (published in an exhibition/sales catalogue in 2000, Best of Bach, plate 32) which is depicted for comparison with Cassin's below.

The bagface was described by the German dealer as 19th century Shahsevan sumakh with extra weft of the Khamseh region (in Best of Bach, 2000). It was later offered to collectors as "one of the oldest" Luri bag faces the dealers knows of and, finally, displayed even "possible Kurdish influence".

I had

once written about this amazing indifference,

"Respective ethnicities are quite different, separated by huge distances, language barriers and high mountain ranges. The Shahsevan claim descent from Oghuz Turks which had invaded Iran in the 10th and 12th centuries. They speak Azeri, a Turkic language. Among Luri (an Iranian language) speaking tribes of the Zagros mountains in Southern Iran are the Boyer Ahmadi and Bakhtiari tribes. Kurds are an Iranian people speaking the Kurdish language. Any intermarriage between these ethnicities is highly unlikely. The bag face in question has a main field most characteristic for Bakhtiari weavings. Two outer borders with its animal or bird heads facing each other (separated by a border displaying stylized rams or blossoms) are on the other hand quite special. The weaving is rather loose, in contrast to common Bakhtiari weavings which, in their bags, usually have more durable pile knotting at the bottom. The patina of the bag may in fact point to old age. How old remains a matter of guessing."

And resuming,

"Coming back to the confusion among dealers about age and provenance. I would agree that lifelong dealing with textiles may put some of them in a position to make claims which might lend them authority. What is missing is certainly any evidence. As long as the origin and history of certain pieces is kept in an obscure state, any claims should be met with basic skepticism."

"Shahsevan" had been a trigger term for antique artifacts from the Transcaucasus, in particular khorjins and mafrashs (bedding beds). Dealers were hopeful of making big earnings as they praised the high quality of sumakh weaving, the surprisingly bright color palette and the often amazing designs. Books by Tanavoli, Azadi & Andrews in the 1980s and later Wertime had spurred a hype for a worldwide run for these artifacts. What appears now on the market and whose provenance (from which collection it stems, in which bazaar it was found and in which condition) is generally hidden should be considered of questionable value. They are usually just reproductions with an "antique" label just attached (or "datable about 1880").

Rug dealers are never scholars, and neither are collectors who, after some time, become inevitably dealers. Scholars are experts who do not need to own "collectibles" to study them.

Apparently, Cassin had collected samples of a group of khorjin faces displaying a grid of hooked devices, see above. Or, wasn't he able to sell them on time, so they stayed in his collection until his death? At least one is outstanding, see below. The lower two probably belong to the same bag which was cut in two halves, a habit, collectors often find tempting, as they disregard the purpose of these, well, commodities in order to sell one and keep the other (thus make more money). I will return to that later.

The three upper khorjin faces are assigned, by the auction house, as Shasavan, mid 19th century or ca. 1875 (lots 19, 23, and 24). The two halves of the bag in the lower row (lots 21 and 22) are also assigned to the Shahsavan, but I doubt that based on the same reasons outlined above. The darker-brown central field and the entire color palette may rather fit to dying traditions in south-west Iran, i.e. again Bakhtiyari/Luri. Of course, this is just guessing. Cassin was smart enough, not to speculate on either detailed provenance or exact age. In contrast, he tried to convince us that there is an intellectual discernable continuum of archaic (the "archetype"), classic, traditional, and commercial periods. I am not sure whether he applied this also to the here displayed khorjin faces.

That (lot 19 in the Cassin sale) is how I would expect a mid 19th century sumakh weaving, which has been used as a bag, would look if well-kept. Jack never ranked the condition of a century-old weaving very high. What matters were execution of the weaving, elegance of the design, brightness of colors and, well, exceptionality. This khorjin is a wonderful example of early Shasavan weaving art. Beautiful, well-done, of great age and maybe the best of this particular group.

The above is a khorjin with this particular design of hooked medallions in a lattice, no doubt by the Shahsevan. I bought it a couple of years ago from a renowned, honest and trustworthy dealer in Istanbul. Again, I would expect this condition of a 150 or 200 years old sumakh. I would also expect overall wear, maybe even local damage, some loss of brightness in colors. I agreed with the dealer that the condition would not rank highest. What matters are certain flaws in the weaver's execution of the design which would rank mine far inferior to Cassin's (lot 19). It doesn't have the former's elegance, and Jack would be pleased to read my ungrudging concession.

I will now turn to three of Jack's most spectacular bag faces in the Cassin sale, one even being a rock star. Jack has written about them extensively at his now defunct websites, and I want to dive a bit deeper in the world wide web in order to retrieve some of his quotes. In particular the story about the rock star (see below) is, in fact, entertaining.

What sets this Shahsevan khorjin (lot 5 in the auction) apart are the four zoomorphic elements, stylized "dragons" (with red eyes!) or rather Simurghs, in the central rectangular field. The most elegant drawing and the fine weave are outstanding, and the overall mellow patina gives an impression of considerable age. The auction house estimates that this khorjin may have been made in the mid or early 19th century.

As Cassin was smart enough to save the more important posts on RugKazbah on

Academia.edu, one may retrieve this text and have a chance to comprehend Jack's thinking.

"The first is the overall compact and pressed-in appearance the Atlantic Collections [Paquin’s] medallion exhibits compared to the open and more spacious “presence” the WAMRI [Cassin’s] medallion captures. Notice there how each element of this complex design both stands alone and is in synthesis with all the others- this creates a real sense of three dimensionality. This doesn’t happen in the other example.

Notice the extra “tucks” the weaver of the WAMRI medallion added to the “octagon” at the center of the medallion, which bythe way, is an octagon in the Atlantic Collection piece but not so here. The addition of these “tucks” not only adds complexity but also three dimensionality.

Notice the four “hooks” within the octagon in the Atlantic Collection soumak really are hooks while in the WAMRI piece they different [sic]. Not only are they more highly articulated but that articulation has added four additional “animal” forms, (see their crests?).

Notice also the weaver of the WAMRI example created a far more graceful and ‘alive’ depiction of the four large and semi-abstract ‘fantastic’ animals above and below this inner medallion within the larger octagonal medallion.

They are the featured icon of these rare soumak bags. This finer drawing line, the addition of the crest that each animal exhibits plus their flowing sinuous style separates them from the leaden and stiff representations seen in the Atlantic Collections bag.

The same is true for the two pairs of extensions attached to the central medallion. The Atlantic Collections weaver was not able to re-create the dynamic and potent iconic structure the WAMRI medallion possesses.

Granted these nuances are, as explained above, difficult for most viewers to see even after they are demonstrated. But the overall majesty and magic the WAMRI medallion manifests should now be apparent, especially if some time is spent studying these medallions with them in mind.

I have no doubt when these two soumak bags would be shown side-by-side even the most skeptical readers of this analysis would believe and see how these and other tiny but telling features of the WAMRI soumak support it's being the prototype and the Atlantic Collection’s piece a copy."

Herrmann's khorjin had been purchased in the mid 1980s by a rug collecting couple, Mitch and Rosalie Rudnick, from the Boston area. They got it from Arky Robbins, Baktiari Gallery, San Francisco, and I will return to that purchase when discussing the next khorjin in the Cassin sale, which I like to call the "rock star". Jack mentioned, somewhere on the RugKazbah discussion board, that the Rudnicks had paid $15k for the piece, an unheard price at the time. The weaver of this stunning but singular korjin (a comparable sample has never surfaced) may have been the Guccio Gucci of the Shasevan. Its purpose was definitely to to be used as a saddle bag. However, either you like it or not. Jack concedes that it was a sensation but called it a pastiche.

Herrmann's (the Rudnick's) khorjin face may not really belong to the group in which Cassin's khorjin is an outstanding example. Plates 18 and, in particular 19 and 20 in Frauenknecht's (1993) picture book

Schahsavan Sumak Taschen would have served better in order to compare Cassin's khorjin. Below is plate 19 in Frauenknecht's book.

Clearly, Cassin's is the superior piece, with finer weaving and more elegantly drawn and distributed animals in the dark-blue main field. The small devices in the octagon in the center are better depicted, for example the palm trees which may not even be recognized as such in plate 19 of Frauenknecht's picture book.

Frauenknecht himself writes the following,

Plate 19

“When looking at this work [the above khorjin face], I always had the feeling that the weaver still knew what she wanted to say. All the elements, whether the main pattern or the small motifs, seem to be meaningful. In it I see representations of semi-nomadic life, similar to a landscape painting by Breughel[sic], only covered with more or less abstract symbols.”

And about plate 20,

“I can't think of much about this bag; it is breathtakingly beautiful. Completely balanced in drawing with lots of space and color. A Rembrandt among the Schahsavan.”

I will come to the hardly bearable blabber of dealers turn authors in the world of antique rug and textile business later.

What follows maybe the most spectacular antique bag by the Shahsevan and its tragic recent history. Jack had been involved since the mid 1980s when he had bought it from

Arky Robbins of the above mentioned Gallery in San Francisco. Remember, that gallery had sold around the same time the above korjin face of Eberhart Herrmann for an astounding $15k.

The below bag was purchased by Jack complete, with even leather edges and fasteners attached. He had published a picture of the complete bag on RugKazbah but that cannot be found anymore.

Jack writes that, when having bought the complete bag from Mr. Robbins in about 1986, it was regarded a collection piece and never to be offered for sale. But when he got to know that the Rudnicks had bought, for a sterling price, Eberhart Herrmann's above khorjin face, he decided to offer them one half of his still complete bag, and guess what, for the same sterling price.

According to

his records, Cassin offered Mdme. Rudnick the khorjin apparently for $15k and when she agreed, he told her that she would be able to buy just one half.

To make a long (and rather funny) story short, Cassin asked for a pair of scissors, cut the complete bag into two halves, offered her the piece with the intact kilim strip in between and got the money. Needless to say that Mdme. Rudnick complained one month later when she met Cassin at a Sotheby's auction (this wasn't the disastrous sale of Jack's Turkmen bags in 1990) that she had paid too much.

The Rudnicks sold their huge collection in 2016 when her wonderful half bag realized $32,500, plus 25% buyer's premium. So, more than $40K. The

auction house had estimated it just between $5000 and $10,000. The Herrmann bag performed much worse. Anyway, it also yielded a higher return, $27,500 plus buyer's premium.

I am sure that the price of Jack's rock star will sky rocket! While I am writing, about 8 days before the live auction, bids have already surpassed $20k (estimate $4,000-$8,000).

There are more outstanding sumakh bag faces in Cassin's collection. He was renowned for searching the best of the particular group and one has to admit that he succeeded in many cases. In the third installment of this series about Jack Cassin, I will turn Anatolian kilims.

So, stay tuned!

Comments